In July, police shot and killed Alton Sterling and Philando Castile — two unarmed Black men — in a 48-hour period. Videos of their deaths, filmed on cellphones by witnesses, went public almost immediately. Protests erupted across the US, and “Black Lives Matter” again became a rallying cry as thousands of people blocked highways, occupied government buildings and demonstrated in city streets. Within hours, a right-wing backlash swept across the nation, fueled by the actions of an unaffiliated US military veteran who shot five police officers at a march in Dallas. Not long afterward, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) national website mysteriously went down.

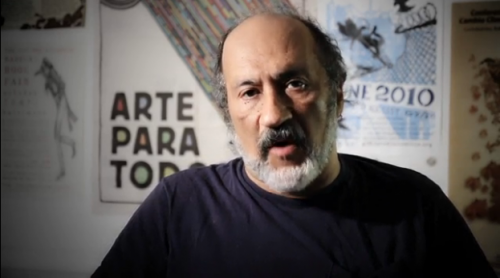

That’s where Alfredo Lopez comes in.

“BLM National got hit with a dedicated distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack,” said the 67-year-old Puerto Rican New Yorker, who in 1995 founded May First/ People Link — a left-wing, membership organization that works on technology-related issues and provides Internet services, such as web hosting, to progressive organizations and individuals.

In a DDoS attack like the one that crashed the Black Lives Matter website, a remote “hit squad” attempts to make an online service unavailable by overwhelming it with traffic from multiple sources. The Black Lives Matter website was hit with more than 15 million connections in one day, according to May First/ People Link.

“After a while the site can’t handle it, and it comes down,” Lopez said. “So does the server it’s on, because the server is getting hit.”

Typically, when a website falls victim to a DDoS attack, the commercial provider hosting that site will simply take it off the Internet, because it’s a threat to the server, Lopez explained. May First/ People Link, however, will return the site to service and keep it online “because it’s essential that the message that’s being blocked continue to get out.”

Black Lives Matter National is a member of May First/ People Link. When their site was attacked, Lopez’s co-workers put in “24-hour days” fighting off the DDoS attacks, he said, using a website protection program created by equalit.ie — a Montreal-based collective that defends free expression and self-determination on the Internet.

“No commercial provider will do that,” Lopez said. “That’s a lot of effort. We provide security for websites and email and everything that almost no one in this industry does. The Black Lives Matter website is up because we kept it online.”

As DDoS attacks have become more common, more activists are taking Internet security more seriously. It’s now fairly common for politically radical groups to be targeted online by their opponents, according to Lopez. The movement for reproductive choice is “continuously” attacked, he added — especially those groups affiliated with the Abortion Now Fund. The Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement for Palestinian solidarity is another high-profile target for right-wing hit squads. May First/ People Link has defended their websites, too. And their membership grows as a result.

“People join when they get freaked,” Lopez said. “They come to us for protection from hit squads.”

May First/ People Link differs from the average web hosting provider in other ways, too. It’s unabashedly left-wing, with a strong utopian streak. It is a member of multiple activist coalitions, including Media Action Grassroots Network (MAGNet), Association for Progressive Communications and US Social Forum. Its members initiate issue-based work groups and sign onto monthly conference calls. It takes part in and puts on social forums, writes statements and joins coalitions. Lopez himself has been a movement leader in social justice circles for over half a century. He seamlessly shifts in conversation from praising a new free, online conference call platform to discussing the potential for technology to topple capitalism.

“Today, you’re constrained by capitalism to being just a fraction of what your potential is,” he said. “Imagine what the world could be like. Technology can actually realize that, so it becomes a facilitator for the realization of people’s imagination. Imagination is essentially the collective planning of possibility. It’s difficult to envision within the context of this society, but within the context of this society, we’re dead. People keep saying, ‘How are going to do that? Capitalism won’t allow you to do this.’ Yeah, well, capitalism won’t allow you to live. You have to think beyond that. You have to start visioning much further.”

He paused.

“I’m not there to say, ‘Here’s how you can fix your email.’ I talk about technology, I talk about Net Neutrality, I talk about surveillance.”

May First/ People Link employs only two techies who respond to requests for email, mailing list and web hosting problem-shooting from more than 800 members (including some 500 organizations). Yearly dues are $100 (individual) or $200 (organization) for access to open source equivalents of “all the major commercial capabilities that you see out there.” That includes cloud software like ownCloud, which is an alternative to Google Docs, and Jitsi, an encrypted teleconferencing program.

“Our job as an organization, particularly our technologists, is to keep tracking all of these free and open source developments, and then to seize them when we can,” said Lopez.

Other techies, Lopez said, who are members of the organization but aren’t paid staff, work on software development and other, broader projects.

Lopez comes from a family of carpenters, and he always loved seeing how things worked, he said. He didn’t expect to end up running a near-broke organization that takes on national security surveillance policies and teaches Leftists to use technology in safer and smarter ways.

“People’s path in life is almost never planned,” he said.

Twenty years ago, Lopez “got interested in Internet work,” he remembered, “because I sensed that there was some potential there. I had a feeling that this was going to blow up. I saw this revolutionary potential.”

Together with two friends, Jamie McClelland and Josué Guillén, Lopez founded an Internet provider, which would become May First/ People Link, to provide web hosting and email to activists. To this day, May First/ People Link relies on its membership fees to cover costs.

If May First/ People Link had more money, Lopez said, it would pay its staff better, hire more people — both techies and movement organizers — and it would bulk up its People of Color Techie program. This one-of-a-kind, year-long training pairs up 6 to 10 young activists of color with technologists and provides one-on-one mentorship and workshops. Trainees learn how install and maintain server operating systems, use programs that make servers accessible to people, develop and maintain networks and projects that use server software, including radio servers, clouds and online chat and communications programs. They work in teams to develop software, build networks and familiarize themselves with administration strategies, as well as think about and act upon issues involved race, racism and technology.

“While the backbone of the Internet is still owned by corporations, the servers that do most of its work are under the control of people called ‘techies,’ and only about 10 percent of all techies are people of color,” reads the May First/ People Link description of its program. “While all computer skills (like using specific software programs) empower individual people, the empowerment of an entire community is based on who controls the core operations of the system. If people of color are excluded from these decisions and from the management of operations, the gap between technology and the experience of people of color can only become greater.”

The program, which launched in 2012, has been on-and-off, due to lack of funds, Lopez said. Money, Lopez said emphatically, is the greatest obstacle that May First/ People Link faces. Foundations tend to stay away, he said, because they often prefer local, small-scale projects that deal with coding and avoid taking positions on issues like Net Neutrality.

“They don’t understand what we’re doing, so we don’t get money,” he said. “We’ve basically built technology structures for our movement and work within the movement to protect the rights of people to use it. We’re trying to get the movement to more effectively use technology. The stage that we’re at right now is trying to mobilize to change society, and technology can expand the mind and help us imagine what the world can be like.”